January 19, 2021

January 19, 2021

The process of drug development involves clinical and nonclinical studies. Nonclinical studies are considered crucial for understanding the safety of new drugs. Before testing a drug in people, Sponsors must first understand whether the drug has the potential to cause serious harm to humans.

Even though the FDA has detailed good laboratory practices (GLPs) for nonclinical studies in 21 CFR Part 58.1: Good Laboratory Practice for Nonclinical Laboratory Studies, it is important to remember that GLPs are intended to assure reliability of the conduct of the study and not to assure that outcomes of the studies will be useful. Sponsors often make oversights or incorrect assumptions with regard to study design or conduct that can delay or increase costs of the drug development process.

Listed below are examples of nine potential failure points that can occur during nonclinical development:

Selecting doses is a decision that should not be made lightly and should take into consideration where you want to end up in relation to your clinical plan. Keep in mind that the FDA has expectations about what doses should be tested; depending on the indication, they typically want to see a dose at which there is no toxicity, as well as a dose that causes toxicity. Often times, Sponsors assume that they have proven safety by choosing doses that do not cause toxicity. What the FDA is looking for in toxicity studies is the identification of potential adverse effects that may need to be monitored during clinical studies. Ideally, the Sponsor will have chosen a dose range that defines the levels of exposure at which adverse effects may occur and is able to demonstrate that there is adequate safety margin for the doses they ultimately want to test in humans.

Drug developers commonly use a limited number of species for rodent and nonrodent toxicity studies. Very often, the rat is the rodent species, and the dog is the non-rodent species. However, Sponsors must give thought to what species to use depending on the nature of the study and clinical indication. For instance, if a topically administered product is being tested, the minipig is often the better choice because minipig skin is morphologically and functionally similar to human skin. There are times where dogs are not the best choice because certain orally-administered compounds and vehicles can cause them to vomit. It’s also important to select at least one species where the compound being tested is pharmacologically active.

GLP-toxicology studies can be costly and time-consuming. Significant program delays may occur if a study needs to be repeated due to unexpectedly high mortality or insufficiently high dosing. To avoid costly repeat studies, Sponsors typically conduct smaller, less expensive, early non-GLP pilot studies to provide toxicology and toxicokinetic data that can be used to help design pivotal toxicology studies. You always want to consider conducting these pilot studies, and it is important to test a sufficient range of dosing conditions so that you can best define how you want to dose the animals in the GLP studies to avoid having to repeat an expensive GLP study.

Nonclinical biomarkers may not always provide additional translational data, but often times they do and having appropriate data for the target organ(s) of toxicity from the early-non-GLP toxicology studies could be helpful prior to moving into GLP studies. Biomarkers can provide a more granular time-course of tissue injury. Sometimes they can also provide information about the mechanism of toxicity. This can be extremely valuable when moving into a clinical study as it helps Sponsors understand if these exploratory biomarkers can/should be evaluated in the clinical study and whether the particular potential mechanism is relevant for humans as opposed to being an animal-specific effect.

For example, if you are developing an injectable, the FDA wants to see that your GLP toxicology studies are done with a formulation that is very similar (if not identical) to the one that you plan to use in humans. If you’re going to use something to help solubilize your molecule in your injectable, the FDA will want to see that the formulation including the solubilizer tested in your animal studies before introducing the formulation (+ solubilizer) into the clinic. The same is true when testing a topical product – the Agency will want to see that the topical formulation is very close to what you are going to use in humans. There are, however, exceptions to this. Maximizing exposure is the key objective in the early non-GLP toxicology studies and may require the use of vehicles that are not recommended for human use. As development proceeds into pivotal studies, it is important to explore vehicles that more closely match what will be used in humans. Ultimately, the Agency will want to understand the toxicity of the entire formulation, not just the active ingredient.

Nonclinical contract research organizations (CROs) perform a lot of studies for many Sponsors. As such, they develop a good general knowledge about standard study designs. Problems can arise when your product has an atypical method of use or pharmacodynamic characteristics that need to be kept in mind when developing a nonclinical program of studies. The Sponsor can tell the CRO these things, but it helps to have a consultant who is familiar with the full clinical and manufacturing development of the product as well as the outcomes of prior nonclinical testing to assure that the design of the proposed study will provide useful data. It is important that when the CRO provides study protocols to sponsors for review, a consultant familiar with the development program weighs in on features of the design that are relevant to the state of the development program and the underlying reason for conducting the study.

All CROs use templates for preparing study reports for clients. In general, these templates are adequate for study reporting. However, you want to make sure that if there is some aspect of the method or outcome that needs highlighting beyond what is typically included in a report, you want to make sure that the CRO goes beyond the template and describes that aspect to your satisfaction. Ultimately, it is good practice to have someone working with the CRO to ensure that the CRO writes the best report possible to support the Sponsor’s clinical plan and FDA expectations.

Often, Sponsors assume that the CRO is going to produce the best possible report and all the Sponsor must do is fact check it. In fact, there is a good deal of context that a sponsor can add to the text that makes the results of the study more understandable and relevant to the development program. This is particularly true with the background and conclusions sections. The FDA appreciates an interpretation of the data in reports. This helps Agency personnel understand the study and assists in drawing conclusions based on the data. It’s not the CROs job to make those interpretations. When there is an explanation for why something needs to be evaluated or why a result was obtained, it is important to ensure it is explained adequately in the study report.

In too many cases, Sponsors look at nonclinical studies as something they need to do to get out of the way so that they can get their product into the clinic. They may want to double-up on studies or condense their nonclinical development program into the shortest time possible. This is not the ideal way to proceed. You need to take time to do thorough pilot studies to understand the toxicity profile before the design of the definitive GLP studies. It’s important to take your time, look at the universe of relevant data, and then design subsequent studies based on the data from the studies that have been completed before.

Are you in the process of developing an FDA-regulated product? Are you preparing to begin nonclinical development for that product? Nonclinical studies are a critical aspect supporting clinical development and getting them right the first time is essential to the success of your product in the long run. That is why we are here to help. For the last 36 years, our experts have been helping our clients develop successful nonclinical programs, ultimately leading to successful interactions with the Agency. Contact us today to learn more about our decades of experience and success and to find out how we can help with your FDA needs.

TAGS: Regulatory Sciences

September 22, 2021

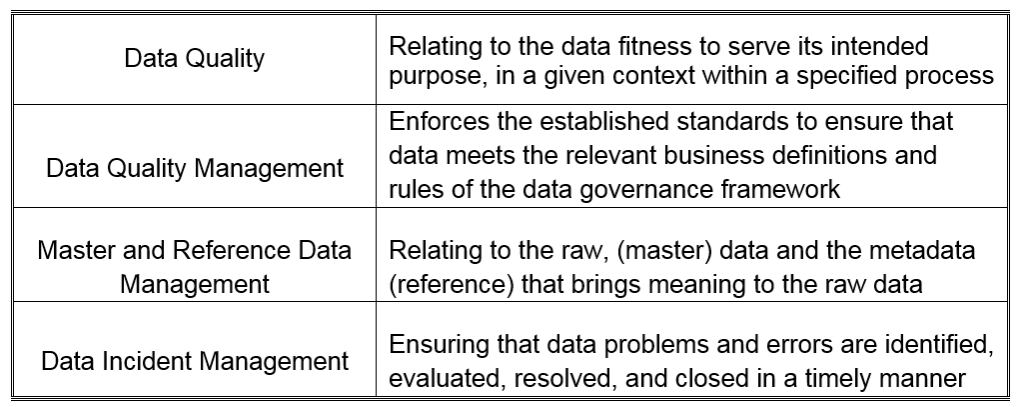

The corporate and quality culture has a significant effect on the maturity level of Data Integrity within a regulated company and should, therefore, be assessed and understood. To achieve the level...

October 15, 2019

The attention of regulatory agencies continues to focus on data integrity, as observed by the increase of FDA observations over the course of the last few years. Having a proper data lifecycle / data...

June 29, 2017

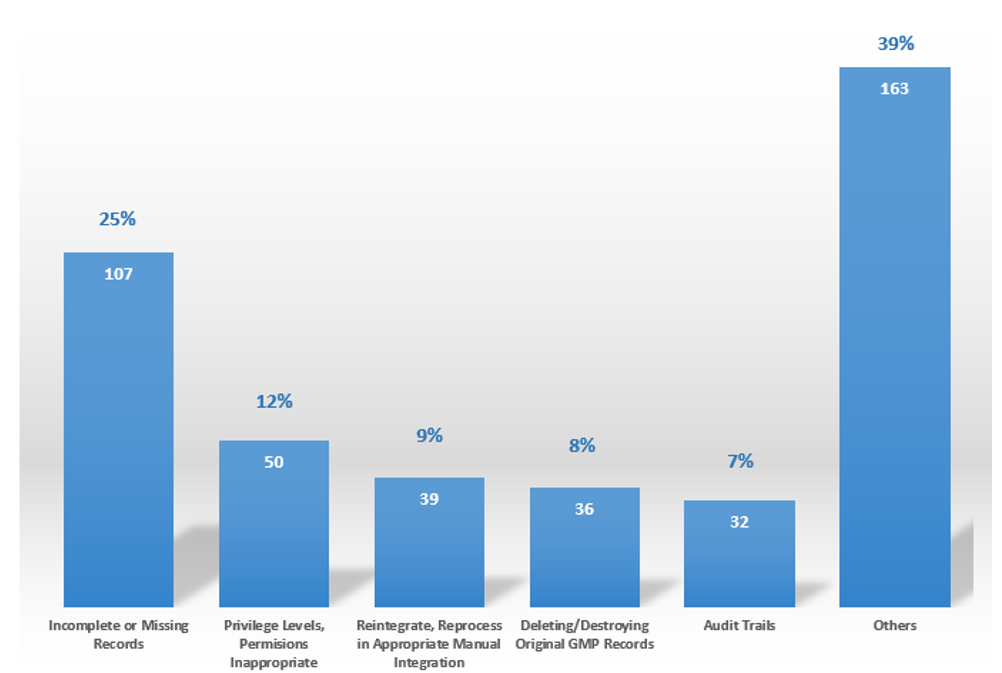

The FDA’s focus on data integrity in recent years has proven that it remains an industry issue. The focus has resulted in significantly increased issuance rates of 483 observations, warning letters,...